Do We Need “IT-Savvy Politicians” for a Data-Driven Digital Nation? ―― Their Role Should Be Governance Responsibility, Not Technical Intervention

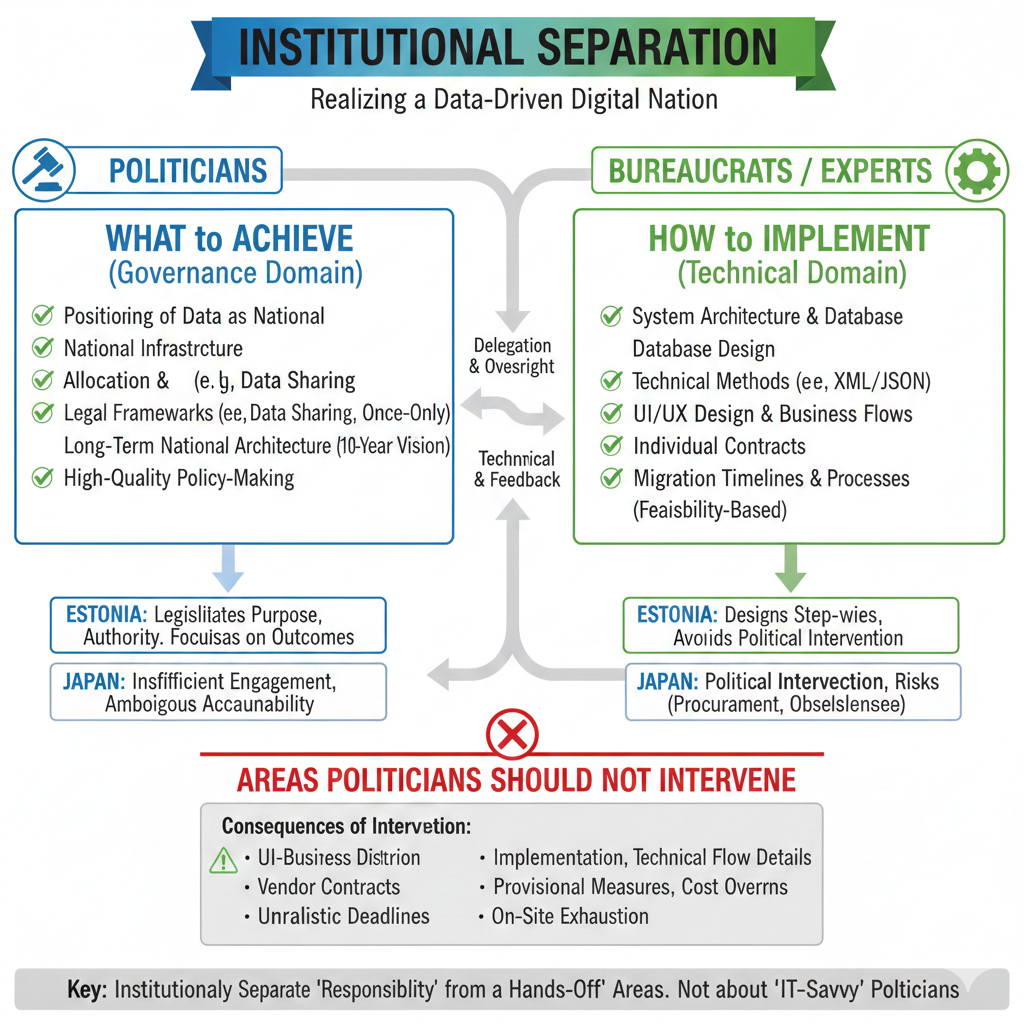

In realizing a data-driven digital nation, politicians do not need to be involved in the design of individual information systems or technical implementation. Rather, it is preferable to design institutions so that politicians are structurally confined to the governance domain and institutionally separated from technical implementation.

On the other hand, politicians should clearly engage in governance areas such as the positioning of data, allocation of authority, accountability, legal frameworks, and long-term national architecture. Above all, it is important to create an environment where politicians can focus on high-quality policy-making and its realization.

In Estonia, the roles of politicians and bureaucrats/experts are clearly separated.

Politicians: What to achieve (purpose, authority, responsibility, legality)

Bureaucrats/Experts: How to implement it (architecture, technology, operations)

This clear separation allows the framework of the decentralized interoperability architecture (X-Road) to be politically guaranteed, while system development such as X-Road is delegated to experts, avoiding political intervention.

In Japan, there is a misconception that “being IT-savvy means being able to judge technical implementation,” which is often used to justify political intervention.

Areas where politicians “should not be involved” are as follows. Political intervention in these areas leads to risks such as procurement irregularities or technological obsolescence.

- System configuration and database design

- Technical methods (e.g., XML vs. JSON)

- UI design and detailed business flows

- Individual vendor contracts

- Politically driven decisions on migration deadlines or schedules without expert feasibility assessments

Determining schedules or completion deadlines for system construction may seem like “policy judgment,” but migration processes and deadlines are inextricably linked to architecture, operations, and technical debt. As a result, they cause issues such as “distortion in implementation, permanent provisional measures, cost increases, and on-site exhaustion.” This becomes “political intervention that decides technology while intending not to.”

In Estonia, legal frameworks are decided by politicians, but migration speed and processes are designed stepwise by experts. Politicians may question the reasons for delays, but they do not predefine unrealistic deadlines detached from technical feasibility.

Areas where politicians “must be involved” are as follows. Politicians do not intervene in system implementation but bear responsibility for the outcomes.

- How to position data as a policy resource and national infrastructure

- Which data can be shared, for what purposes, and to what extent (legal interoperability)

- Allocation of responsibility (who bears accountability)

- Long-term vision (10-year national architecture)

- Separating these from technical choices or individual projects and clarifying them as political responsibilities

- Estonia’s data sovereignty and the once-only principle (information provided only once) were legislated under political leadership.

In Japan, politicians perceived as IT-savvy sometimes step into areas where they “should not be involved,” while in areas where they “must be involved,” their role is often insufficient or accountability is ambiguous.

Issues like troubles with the My Number health insurance card or delays and cost overruns in local government information system standardization can be understood not as technical problems per se, but as results of confusion between governance areas where politics should engage and implementation areas where it should not.

The “Priority Policy Program for Realizing Digital Society,” decided by the Cabinet on June 13, 2025, promotes initiatives such as the Trinity Reform (institutions, operations, systems) and strengthening data governance. Building on this momentum, there is a need to clearly reorganize and institutionally redefine “how politicians should be involved” in realizing a data-driven digital nation.

What is ultimately called into question is not increasing the number of “IT-savvy politicians,” but whether “the areas where politics should take responsibility and the areas where it must keep its hands off are institutionally separated.”